State of HLSL: February 2026

I’ll probably always remember 2025 as the year that I stopped being able to have conversations about future directions for GPU programming without someone slipping the word “neural” into the conversation. While I’m personally skeptical about many applications of neural networks, 2025 is also the year that some really interesting use cases, specifically around realtime graphics, gained attention.

The rise of “neural rendering” (a term I loathe) defined 2025 and dominated the conversation around HLSL this year, but it isn’t the only thing happening in HLSL-land. So let’s talk about the other things first then come back around.

Status of HLSL in Clang

The HLSL teams at Microsoft and Google have continued to make steady progress on

the Clang implementation of HLSL. Clang now supports [RW]Buffer and

[RW]StructuredBuffer resource types and will soon support

[RW]ByteAddressBuffer. The team has continued expanding support for the HLSL

intrinsic functions, and we’re just starting work on graphics shaders which will

include support for shader inputs and outputs, matrix data types, texture

resources and more!

Most of the work that we’re driving is just to bring feature parity with DXC, but I do want to highlight a few areas where we’re investing in significant improvements over DXC.

Better Root Signature Diagnostics

One of the really cool things that got built this year in Clang is the new root signature parser (shout out to Finn Plummer who did this). We get a lot of complaints about root signatures for a lot of reasons, and the weird grammar parsing is just one of the reasons people tend to dislike them. While a longer-term solution to root signatures isn’t currently on our roadmap, the new parser in Clang is pretty awesome and it really shows the kind of quality focus our team is driving.

A key goal of this work was to prioritize great diagnostics coming from the root signature parser with accurate source locations so that if you make a mistake in a root signature the parser will give you as much help as we can to find the error. To enable this, the new root signature parser uses Clang’s utilities for parsing, source locations and diagnostics. This makes it possible for Clang to give diagnostics with accurate source locations in cases where DXC could not.

For example, given the root signatures specified as:

#define BasicValidation \

"StaticSampler(s0, maxAnisotropy = 13)," \

"StaticSampler(s1, maxAnisotropy = 17)," \

"StaticSampler(s2, maxAnisotropy = 13)," \

"StaticSampler(s3, maxAnisotropy = 13)," \

"StaticSampler(s4, maxAnisotropy = 23)," \

"StaticSampler(s5, maxAnisotropy = 13)"

DXC provides the following diagnostic, where the source location points to the line that the preprocessor directive begins on, not necessarily where the error is.

<source>:40:9: error: root signature error - Static sampler: MaxAnisotropy must be in the range [0 to 16]. 17 specified.

The new parser in Clang provides much more context, with specific locations inside the macro definition itself:

<source>:42:4: error: value must be in the range [0, 16]

42 | "StaticSampler(s1, maxAnisotropy = 17)," \

| ^

<source>:45:4: error: value must be in the range [0, 16]

45 | "StaticSampler(s4, maxAnisotropy = 23)," \

| ^

2 errors generated.

You may notice that Clang produced two errors rather than just one. This is another key difference between DXC and Clang’s parsers. The DXC parser aborts on the first error it encounters. This means that if your root signature has multiple errors you need to iterate resolving one then recompiling the shader to see the next error. The new parser in Clang recovers from parsing errors where it can and attempts to continue parsing to provide a more comprehensive set of diagnostics in a single pass.

To demonstrate some of the resilience in Clang’s parser and it’s ability to recover consider the following root signature that has multiple errors, sometimes in the same clauses:

#define Recovery \

"CBV(b0, reported_diag, flags = skipped_diag)," \

"DescriptorTable( " \

" UAV(u0, reported_diag), " \

" SRV(t0, skipped_diag), " \

")," \

"StaticSampler(s0, reported_diag, SRV(t0, reported_diag)"

For this root signature DXC’s parser provides the diagnostic:

<source>:63:9: error: root signature error - Unexpected token 'reported_diag'

#define Recovery \

^

Meanwhile Clang’s new parser identifies multiple errors in a single pass:

<source>:64:12: error: invalid parameter of CBV

64 | "CBV(b0, reported_diag, flags = skipped_diag)," \

| ^

<source>:66:14: error: invalid parameter of UAV

66 | " UAV(u0, reported_diag), " \

| ^

<source>:69:22: error: invalid parameter of StaticSampler

69 | "StaticSampler(s0, reported_diag, SRV(t0, reported_diag)"

| ^

<source>:69:45: error: invalid parameter of SRV

69 | "StaticSampler(s0, reported_diag, SRV(t0, reported_diag)"

| ^

4 errors generated.

Clang’s parser can’t always detect all the errors as the parsing context may be incomplete, but it does a much better job than DXC’s parser.

We really think this kind of quality-of-life improvement will make Clang a much better tool for our users and we’re really excited to see some of this quality focus coming to life. Both of the examples above I pulled from a Compiler Explorer demo Finn created that shows off the differences in diagnostics between Clang and DXC really well. Take a look at that for more examples and keep playing with it.

Offload Test Suite

Another big area that we’ve been investing in is our testing infrastructure. DXC’s infrastructure for testing shader execution only supports DirectX on Windows, which turns out to be a pretty big limitation as we’re increasingly viewing HLSL as a cross-platform language. Further, the infrastructure is very tightly connected to DXC in a way that doesn’t make it easy to use with Clang.

To address these limitations we’ve built a new testing infrastructure in LLVM called the Offload Test Suite. The new infrastructure is dependent on LLVM for some utilities, but the test execution is decoupled from the compiler and source language allowing us to run the same tests with DXC and Clang. Additionally, the new infrastructure supports DirectX, Vulkan and Metal giving us wide testing coverage.

We’re using this new infrastructure to not only expand our testing of the Clang compiler implementation, but also to ensure that shaders compiled with Clang behave the same as when they are compiled with DXC. We hope this will make it a smoother migration path for our users.

If you’re interested to learn more about this infrastructure, I gave a talk last fall at the LLVM Developer Meeting about it and how the HLSL team has integrated it to our workflows.

Standardizing HLSL!

Note: I wrote about standardizing HLSL on the DirectX blog. If you prefer to read a more “official” (read humorless and devoid of personality or memes) version of this go there. Otherwise strap in!

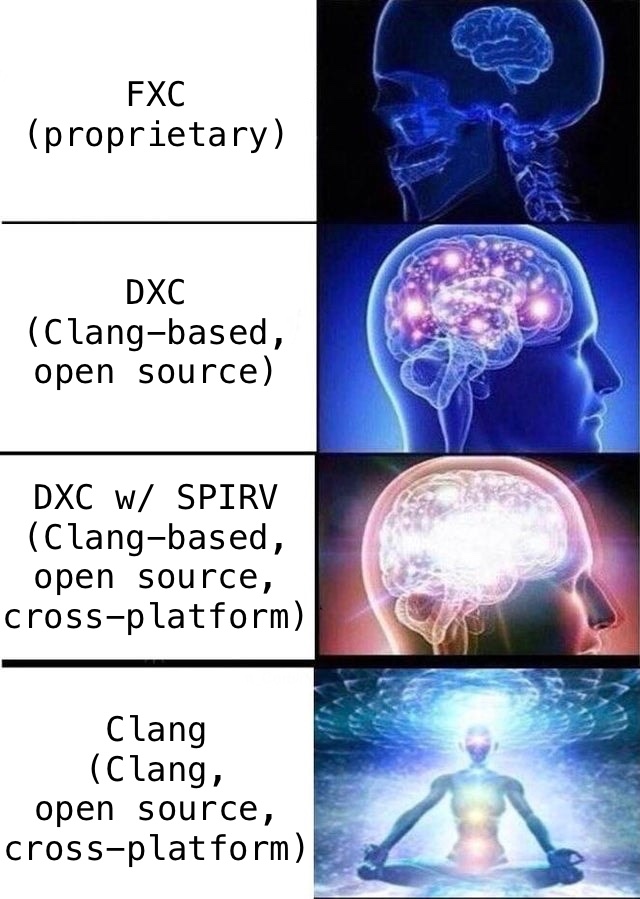

The development in HLSL that I’m most excited about coming into 2026 is that we’ve started the process of forming a committee to standardize HLSL. I’ve built my career around open source software, and deeply believe that some types of software just should not be proprietary, moving to standardize HLSL is the only path I see forward for HLSL to evolve and thrive. I’ve said this a few times, but I’ll reiterate it here: the future of HLSL is cross-platform and open.

This has been a huge effort for me personally as I’ve been working to win hearts and minds across Microsoft as well as strengthening partnerships across the industry. Microsoft has some reputations that we’re working to overcome and I’ve put a lot of my personal reputation out to signal that we’re serious about this.

Why are we doing this?

In my experience, compilers and programming languages are just too complicated and don’t bring enough differentiating value for businesses to justify adequately staffing compiler teams to build proprietary compilers at quality and scale that compete against open source alternatives. This is especially true for languages as complex as C++ (which HLSL is trending toward).

Inadequate staffing for HLSL has been a huge problem for our team. We have a massive pressure to constantly expose new shader model features, and we have never had a large enough team to both expose new hardware features and evolve HLSL itself to make users more productive. This has led to a lot of short sighted decisions along the way. We’ve taken shortcuts and accrued massive technical debt, the most obvious bit of which is DXC being locked to LLVM 3.7 which is now over a decade old.

The bare truth is that a good programming language and compiler is price of admission for a platform, but it isn’t going to sell more hardware or software licenses. That said, a bad programming language or compiler can burden software developers so much that it impairs their ability to ship quality software, which will adversely impact sales.

While I don’t think the HLSL compiler is (yet) out of date and “bad” enough to be a real liability, it is trending that direction so we really need to fix it, and in fixing it we need to shift our development model for HLSL to be more sustainable with reasonable investment of resources.

This is all business speak for: embrace open source, build broad partnerships, and build a healthy community.

What benefit will a standard provide for users?

Being unable to invest sufficiently in evolving HLSL itself and in quality toolchain features has contributed to some long-lasting industry problems that have at times seemed intractable. One clear example is the complexity of shader build pipelines.

When you build a cross-platform application’s CPU code you can generally use the same language (and often compiler) for the bulk of your application logic. Concretely, if you’re building a game for Windows, Linux, macOS, Xbox, Playstation and Nintendo; you can write your CPU code in C and C++ and you can use Clang as the compiler. You may have some platform-specific bits in your C/C++ code, but most of the code is easily shared. The same is not strictly true for GPU programming.

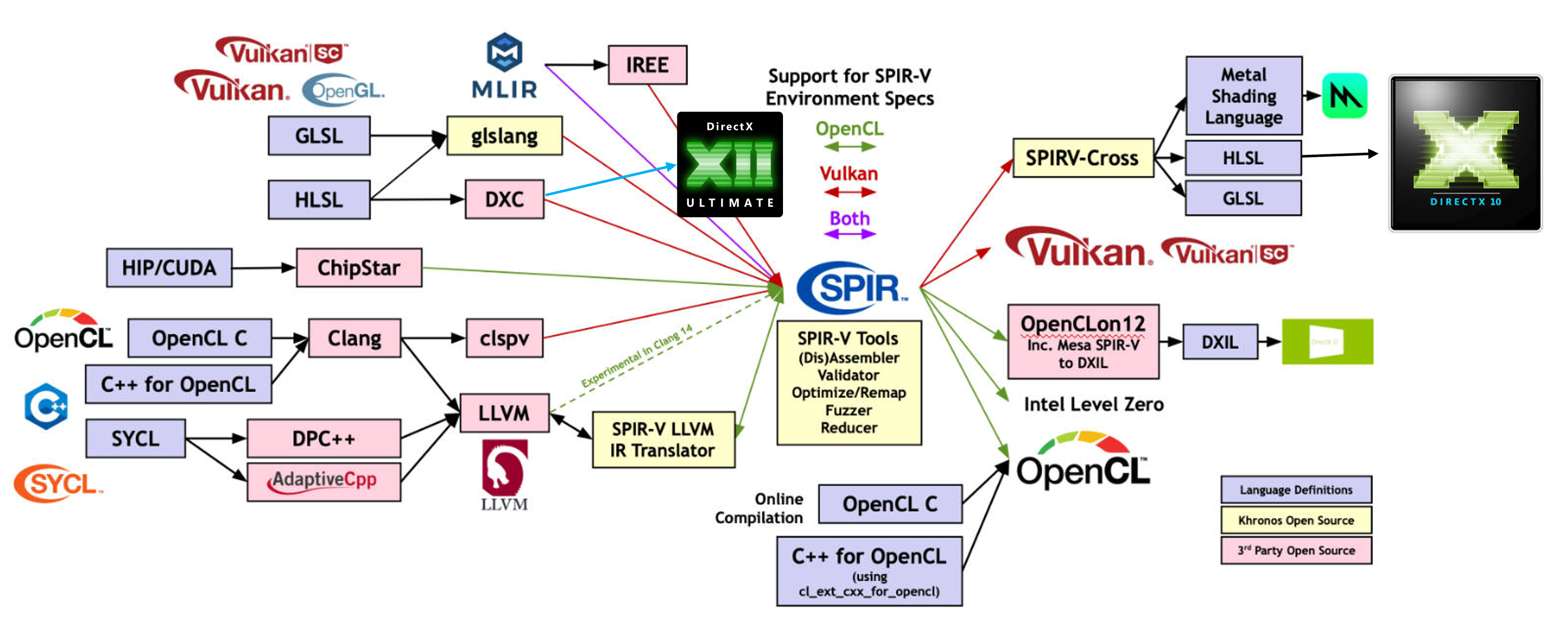

The Khronos Group, through its members and community, has done amazing work building a cross-platform pipeline for GPU programs, but it is immensely complex. Consider my modified version of the SPIRV ecosystem diagram from Khronos, where I’ve added DirectX into the picture:

It’s impressive how many source languages you can choose from (on the left), and how many target runtimes you can execute on top of (on the right). The problem is the number of (lossy) translation layers in the middle. SPIRV-Cross in particular is load-bearing in a lot of shader build pipelines, and it destroys debug information (mapping of final executable code to source lines), which makes shader debugging and profiling extremely difficult.

The absence of unifying tooling which led to this ecosystem state has caused cross-platform game engines to develop their own complex shader build pipelines. I’ve been working in this space a long time and I still get horrified when I hear about how developers actually build shaders for their titles.

Shader build pipelines for AAA engines are complex Rube Goldberg machines that we all put up with in the name of maintaining productivity. Microsoft will not sell more XBoxes or Windows licenses if we fix this problem, so the problem gets ignored… Until now.

Today we already have a native build pipeline for HLSL using DXC and Clang to build shaders for DirectX and Vulkan. We also have a native-ish path for Metal through the Metal Shader Converter, which is an IR->IR translator that preserves accurate debug information and enables HLSL to be used with Apple’s native shader debugging and profiling tools (which is crazy impressive!).

My sincere hope is that by standardizing HLSL in conjunction with our integration of HLSL into Clang we’ll build a broad community around HLSL that prioritizes cross-platform support, high quality tooling, and language evolution. Our ultimate goal is to build broad industry partnerships to ensure that all HLSL users get the best tooling possible.

Hey Apple, Sony and Nintendo: come join us!

Don’t standard committees make things slow?

In conversations I tend to use the term “deliberate” to describe how I would like to see HLSL evolve. Historically, I think we’ve allowed the language to evolve haphazardly without a framing process that required us to think through the short and long term implications of new features. We’ve at times moved too slowly and at other times moved too fast. This both leaves us behind in terms of useful feature sets and lacking in quality. As a notable example, HLSL 2021 introduced more bugs than features, and we’ve now spent years addressing them.

I believe that adopting a standard process will force us to evolve HLSL within a process designed to make us be thoughtful and deliberate about the features we add (and remove) from HLSL. This process may at times be slower than we could be without it, and it may be slower than other competing languages, but I believe it will produce a higher quality result which is in the best interests of everyone. I also believe that by doing this under an international standardization body, we will have a framework to keep us honest and curtail our base instincts that may lead us to make rapid and flawed decisions.

I bristle when I hear people talk about “rapid innovation” in programming languages or compilers. There are certainly types of software where rapid innovation may benefit users, but infrastructural software that people depend on needs a level of stability and reliability that is at odds with the “move fast and break things” model.

I can’t imagine anyone wants to integrate an experimental tool in a load-bearing capacity to a production codebase, and following on from that I believe that most of HLSL’s users want to be able to depend on HLSL being stable so that the code they write in HLSL today will work as expected in the future. The worst thing we could do is make fundamental changes to the semantics of HLSL without considering our users and the impact on them, and a standard process will provide a forum for our users to have a voice and a framework to keep us honest as we evolve HLSL for the future.

Okay, how does this really work?

The newly formed Technical Committee 57 under Ecma International will focus on specifying and standardizing the core HLSL language. This effort will focus initially on core behaviors (grammar, basic data types, conversion rules, overload resolution, etc) and a limited set of common features that are across all API targets.

As the committee evolves we hope that it will provide energy around evolving HLSL into a better language while also solidifying it as a cross-platform standard that is not locked to Microsoft platforms.

The committee will operate almost entirely in public and on GitHub, but meetings will only be open to Ecma members and invited experts. We invite everyone to follow along with our public work and contribute to the process!

Neural Rendering

I guess I’ve delayed talking about “Neural Rendering” enough and I should just get this over with. Personally I hate this term because I’m constantly fighting with people to explain that from a compiler and language perspective “neural rendering” isn’t any different from any other neural network evaluation, and it’s all just linear algebra on big multi-dimensional matrices… but alas I’m just an old man yelling.

We do have some big work from last year and ongoing around neural network evaluation. Last year we released a preview of the D3D12 Cooperative Vector feature which enabled evaluation of small neural networks in rendering and compute workloads. After a great deal of soul searching in the fall we decided the feature wasn’t quite ready for primetime, but we’ve been actively working on bringing the capabilities of Cooperative Vector, as well as a more capable replacement for Wave Matrix (which we previewed back in 2023 but didn’t release in SM 6.8).

The new feature, boringly named Linear Algebra (or LinAlg for short) includes both the features of Cooperative Vector, and the features of Wave Matrix. We’ve worked to align the feature more closely with other APIs (read Vulkan) so that our new feature can someday be used with both Vulkan and DirectX via HLSL (and maybe Metal too if Apple aligns). This will enable WebGPU to use it to implement their proposed Subgroup Matrix feature for browsers on Windows.

Regardless of how you feel about GenAI or LLMs (I’m a skeptic), it is clear that neural networks have more and more useful applications in graphics programming. There’s a lot of excitement about neural networks for texture compression, radiance caching, path tracing, denoising, and upscaling. For all these applications and more it’s super important that HLSL be able to efficiently lower these algorithms so that shader authors can take full advantage of modern GPU hardware.

One thing I’m excited about is the capability of neural networks to approximate complex functions. In a few years when matrix multiplication and accumulation hardware trickles down to lower-end GPU parts and proliferates across install bases, function approximation may be a valuable technique for enabling higher fidelity rendering techniques on lower-end hardware at acceptable frame rates.

Parting Thoughts

If you made it this far: congratulations! I’ve droned on a lot and I won’t keep you long here. There are a few key themes I’m pushing for HLSL in 2026 which I’ll state clearly even though they are represented in all the text above.

Cross-platform and Open

The future of HLSL is cross-platform and open. That means open source, it means an open specification with a royalty-free patent and IP policy. It means we will welcome contributions from everyone everywhere.

Quality, Quality, Quality

We cannot sacrifice quality for expediency or flashiness. We’ve been burned time and again by shortcuts and lax quality standards, and that pain spreads to our users. We’ve worked really hard to bring a higher standard of quality to everything we do in HLSL whether that is our compiler implementation, our designs for new features, or our draft language specification. We will continue making those investments in quality, and we will continue to have communities to help keep us honest along the way.

HLSL Exists to Serve Users

The thing that makes HLSL a valuable piece of technology is how widely used it is. We will focus on engaging with our users, responding to their feedback, and prioritizing their concerns. We won’t always give each individual user all the things they want because we do have to take a more wholistic look across our whole user base, but our central motivation must be to empower our users to be productive and to leverage our tools to make their applications the best they can be.